The Marshmallow Test is a Lie

Walter Mischel's TED talk → Failure = a Case Study in WYSIATI

Surely you’ve A) heard of The Marshmallow Test and B) are possibly annoyed by it. Perhaps you’ve joked on more than one occasion that you would have failed it.

I’m happy to tell you that not only is it bullshit, it’s such bullshit that it may be my new favorite way to explain everything that’s wrong with psychology and academia and possibly the world.1

A researcher at Stanford named Walter Mischel began testing kids’ ability to delay gratification. In his seminal study, he placed children in front of a piece of candy, and told them that if they could hold off eating it until one of the researchers returned—roughly 15 minutes—they’d be rewarded with two pieces of candy. So, one now or two later?

According to the oft-repeated conclusions, the ability to wait for the second marshmallow predicted higher SAT scores and more advanced careers. As adults, they were less likely to abuse substances or become obese—they even had longer-lasting relationships and better credit scores. They could please multiple women, win that PTA election, raise serious seed funding, and train a seeing eye dog all in one night. The New Yorker ran a typically flattering and uncritical rundown, complete with its requisite “ONE NEAT TRICK TO LIFE” takeaway:

The key, it turns out, is learning to mentally “cool” what Mischel calls the “hot” aspects of your environment: the things that pull you away from your goal. Cooling can be accomplished by putting the object at an imaginary distance (a photograph isn’t a treat), or by re-framing it (picturing marshmallows as clouds not candy).

Got that? To succeed at life, just ignore everything that might pull you away from your goal.2 Easy peasy lemon squeezy 😃

But wait! There’s more

You’re never going to believe this, but—despite what Mischel and his ilk have said for decades—THERE’S MORE TO PREDICTING LIFE OUTCOMES THAN ONE STUPID FUCKING PIECE OF CANDY. A litany of problems plagued the study that went unnoticed/undiscussed for years; my favorite overview is here.3

In attempts to replicate the original finding, “While successes at the marshmallow test at age 4 did predict achievement at age 15, the size of the correlation was half that of the original paper. And the correlation almost vanished when Watts and his colleagues controlled for factors like family background and intelligence.”

While Mischel had us all thinking that Waiting → Success, it’s more like Having a successful family → Success.

“With the marshmallow waiting times, we found no statistically meaningful relationships with any of the outcomes that we studied,” UCLA Anderson’s Daniel Benjamin.

The Other Marshmallow Test

A similar study was conducted in 1970 with children from disadvantaged homes. (Read: parents on welfare or free lunch recipients) Those kids were much less likely to wait (3/15 waited, compared to 11/15 kids whose parents weren’t on welfare).4 But after that initial trial, the impulsive kids were actually shown that additional candy—real life proof of what they would have received, had they waited. This single, tiny intervention (seeing that candy bar in real life!) was enough to make all of those kids wait in following trials.

“An interesting and perhaps more important analysis… indicates that disadvantaged children cannot categorically be termed ‘nondelayers.’”5

If waiting was really crucial to survival and genetic, then how could a simple sentence magically turn subjects into models of patience? I interviewed Laura Michaelson years ago, who found in “Delaying gratification depends on social trust” that making kids doubt their ability to trust researchers instilled impatience:

“Most of the other people who have prominent theories about self-control and delaying gratification don’t acknowledge the social factors at all. Mischel, who was the pioneer of his field, emphasized trust for decades but didn’t touch it experimentally. Most of the other prominent theories don’t mention it at all.”

What looks like irrational behavior usually makes sense when you consider someone’s life history.

This is rule #1 of systems thinking: Remember that others are acting rationally from their own perspective. Given what they know, the pressures they are under, and the organizational structures that are influencing them, they are doing the best they can. Give others the benefit of the doubt.

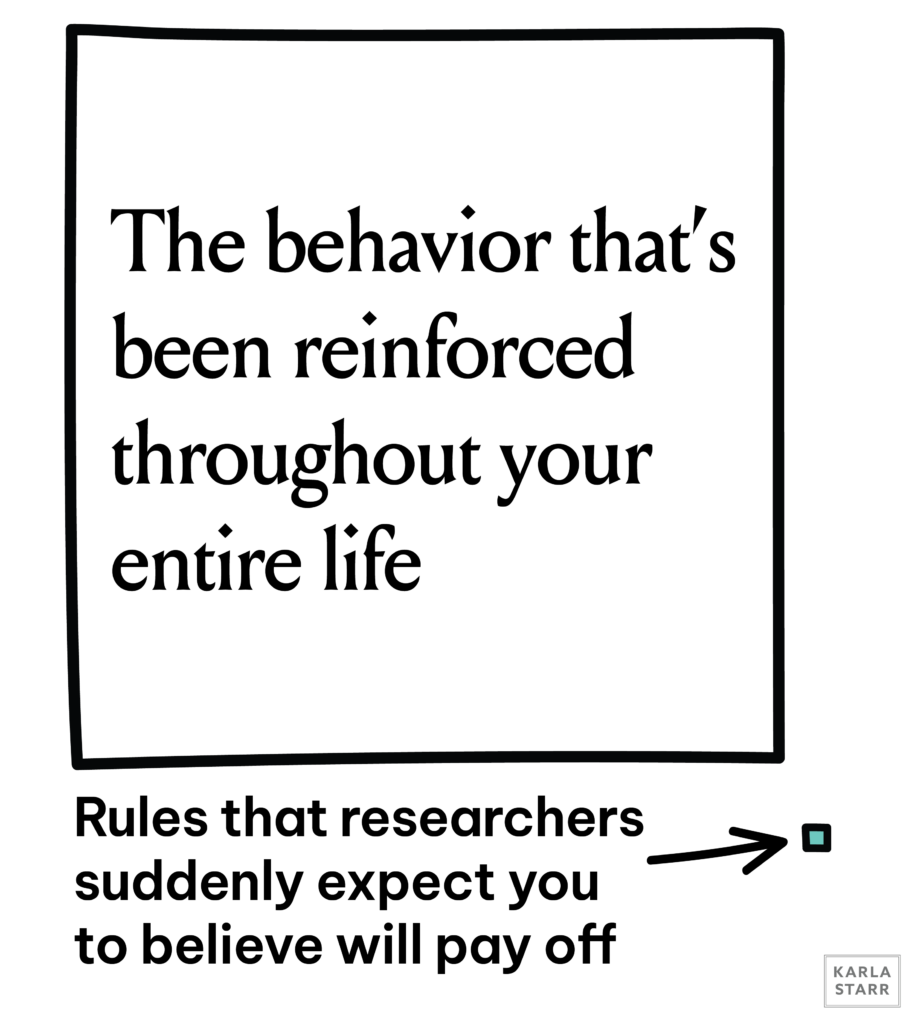

What if you’d repeatedly seen people wait for a marshmallow and come up empty-handed? What if marshmallow-promising adults never followed through? You’d have a perfectly rational reason to doubt the value of waiting or trusting others, not a character flaw.

The existence of different types… makes it inappropriate to compare individuals on a unidimensional continuum of “better” versus “worse” self-regulation. Self-regulation instead emerges as an adaptive coaction between an individual and his or her specific context.6

The Bias of the Fucking Researchers

The brain evolved to get decent answers in an energy-efficient way; rather than search for all of the information, we use whatever is available—our brain is a “machine for jumping to conclusions.” We assume that What We See Is All There Is, which is a pretty good summary of what’s wrong with the Mischel study: researchers apparently assume that children are black boxes, given the same life lessons; that their data points measure the totality of what is needed to draw conclusions; that someone’s life can be separated into discrete parts; that correlation equals causation.

This hubris and failure to consider how different other people’s lives are could be an unintended consequence of the long, slow death march towards academic tenure and the publishing process, which eliminates the vast majority of humanity:

The ability (and privilege) to go to college for an academic pursuit, rather than a trade

The ability (and privilege) to not have to support others immediately afterwards and think that applying to graduate school would be a financially sound decision

The privilege of being able to spend unpaid time in a psychology lab in college

The privilege of having all of the time to fill out graduate school applications, write essays, conduct unpaid research

The ability to go to graduate school (which pays nothing)

Finishing and successfully defending your Ph.D. dissertation

Applying to faculty positions, working until you get tenure, getting grant money, publishing… (this step is what—7-10 years?)

Even for those who weren’t born into privilege and worked their way up to professorships, spending so much time in an environment as relatively stable as the university system makes it easy to forget the daily realities of what other lives are like—which influence expectations and daily behavior.7 The fact that researchers never thought to ponder other reasons for the alleged impatience or shitty credit scores speaks volumes about the research.

Imagine if researchers leaned in to the situation with curiosity and a genuine desire to help, rather than a tone of scorn, judgment, and desire to publish papers? What if they realized that they are, like the rest of us, biased and prone to errors and groupthink?

There Still Isn’t “One Neat Trick”

They might have seen the kids’ failure to wait as a canary in the coal mine—the inevitable effect of experiencing repeated, disappointing interactions with caregivers and role models during crucial developmental periods so much that they can’t even trust scientists.

Thinking “all you need to do in order to achieve success is wait!” smacks of elitism, a lack of empathy, and disdain. Like most studies that catch on, it’s blaming a mindset for life failures—a simple salve, that ONE NEAT TRICK. It’s also in line with why we remember some stories, myths, and urban legends: it’s minimally counterintuitive, or “most advanced, yet acceptable”: a slightly surprising answer that’s right at the edge of what we can believe.

One of the things I find ridiculous about well-intentioned organizations like The Character Lab is the complete failure to understand the daily realities of other people’s lives. I did not need to learn about “the benefits of growth mindset and delay of gratification!” when I was young: I needed someone to wipe my memory of all of the times I was made to think (by my caregivers!) that I was a fundamentally flawed failure. I needed to get teleported into a safe, stable environment with nurturing and encouraging adults. I did not need a lesson on waiting.

Kids in unstable environments surrounded by shitty adults cannot simply “learn to mentally “cool” what Mischel calls the “hot” aspects of your environment: the things that pull you away from your goal.” I never had big goals, aspirational role models, examples of how to achieve such things, or the belief that I could do much to begin with.8

When an Entire Generation Doesn’t Get the Marshmallow

In “Growing Up in a Recession,”9 economists found that shocks can affect an entire generation’s ability to trust in future outcomes:

We find that individuals who experienced a recession when young believe that success in life depends more on luck than effort, support more government redistribution, and tend to vote for left-wing parties. The effect of recessions on beliefs is long-lasting.

ISN’T THAT INTERESTING???

Click the heart like no one’s watching.

Subscribe like you’ve never received a shitty email.

Share like everyone will love it.

Email me at hello@kstarr.com because why the hell not?

This is what happens when you pair me with an old narcissistic white guy who gives overly simplistic answers without questioning the behavioral science research because it’s made him money for decades. You realize that he and the self-help industrial complex are bullshit.

You know, draw the rest of the fucking owl.

Jessica McCrory Calarco. “Why Rich Kids Are So Good at the Marshmallow Test: Affluence—not willpower—seems to be what’s behind some kids’ capacity to delay gratification.” The Atlantic.

Richard T. Walls and Tennie S. Smith. “Development of Preference for Delayed Reinforcement in Disadvantaged Children.” Journal of Educational Psychology 61, no. 2 (1970): 118-123.

Walter Mischel. “Father-Absence and Delay of Gratification: Cross-Cultural Comparisons.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 63, no. 1 (1961): 116-124.

“Development and Self-Regulation,” Megan M. McClelland et al., Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, p. 548. PDF of the book is available here.

And do not even think about giving me this “universities are so unstable, they might pull my funding!” bullshit, people.

Paola Giuliano and Antonio Spilimbergo. “Growing up in a Recession.” Review of Economic Studies 81, no. 2 (2014): 787-817.

Thank you (as always!!!) for expressing so clearly what I’ve been thinking for a long time…