It's Easier to Blame Facebook Than the Economy

The Investment Theory of Commitment and Not Seeing the Big Picture Beyond Your Own Lawn

If you don’t want to read this, I get it. As an alternative, may I suggest David Byrne’s online news magazine Reasons to Be Cheerful. Or the art-maker Jackson Pollock. Or I Thought I Would Have Accomplished a Lot More Today and Also By the Time I Was Thirty-Five. Or this Simple Sabotage Field Manual.

A few days ago, The Atlantic published “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid” from a man who once—while holding an ice cream cone in Washington Square Park—leaned in and told me that “no one wants to admit that stereotypes are true.” That author, NYU professor Jon Haidt, published The Coddling of the American Mind a few years later.

Haidt has perfected what I call “Get Off of My Lawn-ism,” or finding ways to rationalize and codify the idea that things used to be perfect until [shaking fist] kids came and messed everything up. The market for Get Off My Lawn-ism is huge; in addition to seven children, my grandparents left behind several copies of every Tom Brokaw book ever published. What old white guy doesn’t miss the days when they could use the slang they grew up using, without risk of censure? What percentage of Boomers (and beyond) think that the internet is ruining all the things?

Here’s the main thesis of Haidt’s essay: 1

Social scientists have identified at least three major forces that collectively bind together successful democracies: social capital (extensive social networks with high levels of trust), strong institutions, and shared stories. Social media has weakened all three. To see how, we must understand how social media changed over time—and especially in the several years following 2009.

Let me start by saying that I HATE SOCIAL MEDIA WITH THE PASSION OF 10,000 FIERY SUNS. Just so we’re clear. But Haidt blames the Retweet function and Like button on all the world’s ills: a democracy gone wrong, the spread of misinformation, conspiracy theories, etc. etc. Yes, Facebook fucking sucks, I think the company should burn in hell for its role in the mental health of teenagers and inciting unrest abroad. While the only news I’ve ever gotten from Facebook is that a) most of my former high school classmates have kids, and b) everyone I’ve ever known has gained weight, it’s scary to see many people use it as a news portal.

I’m increasingly blown away by how easy it is to live in a completely different world than your neighbor, on the basis of differing subscriptions and algorithmic wormholes. Case in point: my own brother (and neighbor!) is not getting vaccinated. We may share DNA, but we do not share a worldview.

And yet, at no point did either of us log onto Facebook and think: “Tell me, Facebook, what is it you plan to make me believe with my one wild and precious life?”

It’s the untethered times in our life when we lack a strong anchor—a sense of belonging, clear goals, outside ties, accountability—where we can get swept up in something new. In system dynamics, this source of gravitational pull is called an attractor. No one joins a cult when they love their current church and would risk losing friends or community by switching. Mutual love and trust tend to avoid wandering eyes and the suspicion of infidelity.

Like many psychologists, Haidt’s insistence on focusing on the actors and the immediate situation ignores the greater context; everyone lives in a complex system, affected by tons of factors. Everyone thinks that they’re being rational, and truly empathizing with people requires zooming out and looking at the larger factors at play.

The Investment Theory of Commitment

The investment theory of commitment is my all-time favorite way to explain seemingly-irrational decisions to stay the course or switch to something new. Relationship researcher Caryl Rusbult developed the model in the ‘70s, amidst the lingering effects of the Vietnam War, persistence that defied rational cost-benefit analysis.

The three main factors affecting our decision to stick with A:

Satisfaction with A (compared to our expectations)

Sunk costs (how much time/etc., we’ve already invested, or what we’d lose if we left A)

Quality of alternatives (whether real or just perceived)

Another way to think of it is “value of A, value of B, and the cost of switching.”

Haidt never touches the big question: what would make people start to believe in these things in the first place? THEY’RE UNHAPPY WITH THE WAY THINGS ARE. The more we see (mis)information, the less it shocks; we’re more likely to assume that it’s true. Social media is speeding up the feedback loop, fomenting outrage, and highlighting differences—but correcting Facebook will only be a temporary fix without addressing the underlying cause.

Trust in social institutions has been declining since the ‘60s:

Everyone I know who isn’t vaccinated, or has what might be called “non-mainstream beliefs,” is angry and lacks trust in the social contract.

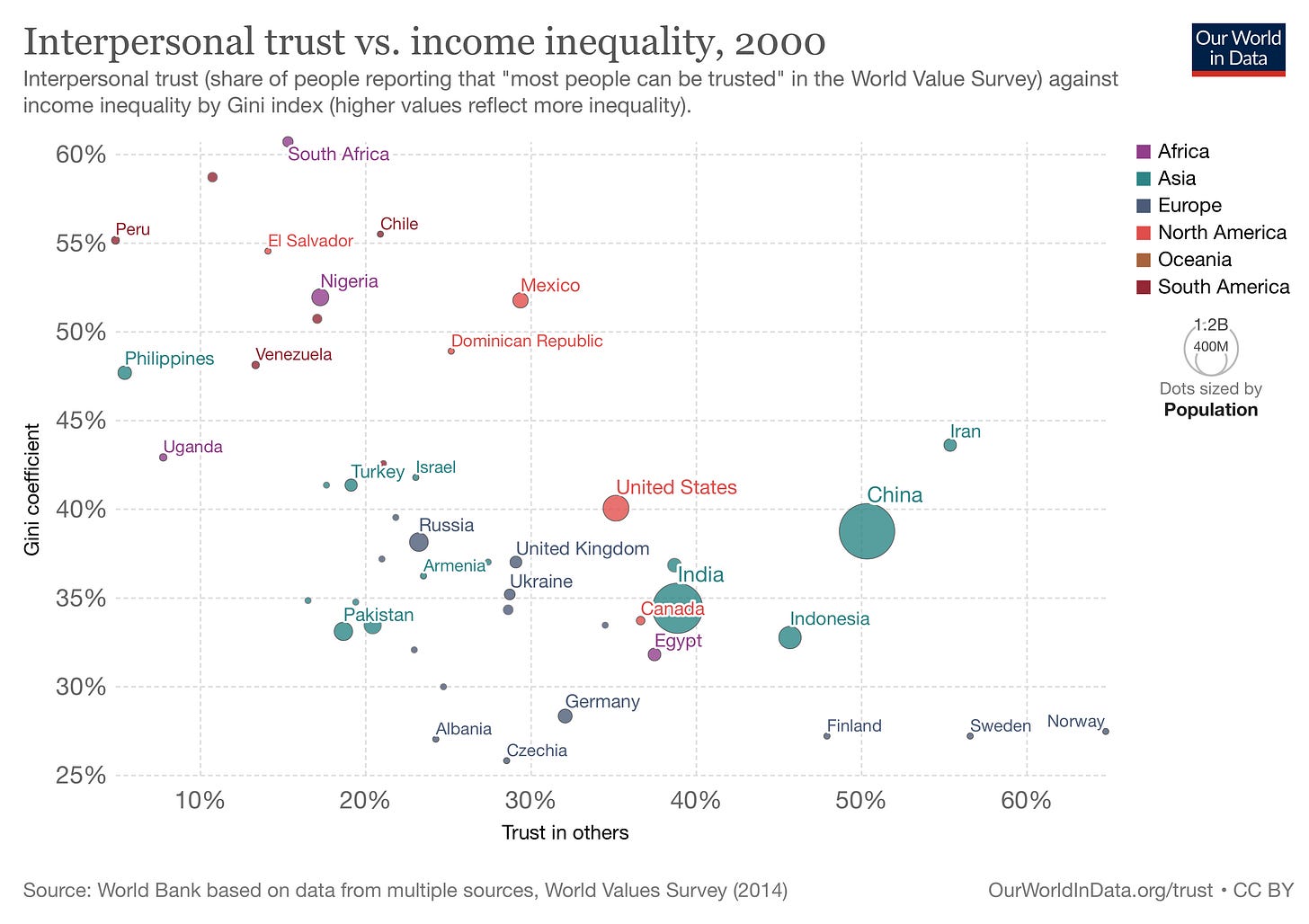

Income inequality is inversely correlated to trust

Humans, unlike other primates, share the spoils of their labor fairly after collaborating; this tendency allows us to create the kind of large-scale cooperation and trust that, in turn, create society. The U.S. is the only industrialized country without universal health care, and our system is designed to maximize profits over health. Four out of five people around the world don’t think the system is geared towards serving their interests, according to the Edelman Trust Barometer (the same survey cited by Haidt), largely because of how much money influences the democratic process.

If the health care system and the government are prioritizing the interests of the wealthy over the health and well-being of its citizenry, they’re openly failing to share the spoils fairly—the very kind of behavior that we, as a species, are prone to punish and cast out of society. The media is so skewed—thanks to a blend of layoffs, prioritizing profit, and being culturally centered in urban areas—that Trump’s victory in 2016 caught everyone off-guard.2 The media landscape, not just the social media landscape, is fractured, biased, and click-based. We’re angry because the social institutions are breaking the social contract, but feel powerless to do anything about it (because we don’t have the kind of money). Meanwhile, our own economic situation is precarious, at best.

And so, the investment theory of commitment also applies to worldviews: believing in a skewed version of reality (that other people are all to blame; that the media is lying; that the government sucks and we shouldn’t believe it) becomes easier when the reality that we’re presented with is, to put it mildly, unsatisfactory.

It’s easy to see how other people are biased, but we all are. Haidt’s article points to a target we can all agree on (social media SUCKS), while missing the underlying causes—because when you’re a well-compensated, well-respected individual, of course you think the system is fair. (I was surprised to get an advanced copy of this book in the mail and discover that my examples about the environment, the gender wage gap, and generational wealth gap were missing.)

No one questions the fairness of a system that places them on a pedestal.

Countries with higher income inequality tend to report lower levels of both interpersonal and social trust, eroding willingness to participate in the social contract. But this isn’t a message we’re ever going to hear from a wealthy person writing for an elite institution who wants to get a lot of clicks, sell a lot of books, and get invited to give lectures for large corporations.

It’s easier to have people rally around Facebook than the economy—it’s something concrete that we all hate and feel empowered to actually do something about. Haidt’s suggestion:

The most reliable cure for confirmation bias is interaction with people who don’t share your beliefs.

Maybe, I dunno, he could start taking that advice.

Don’t be shy! I value feedback at hello@kstarr.com

If you enjoyed it, please spread the word or click the heart button. ❤️

If you can’t read it, consider this handy tool.

It’s a bit like catching your “I’m working late again” spouse with someone else at the grocery store: if they’re lying about this super-obvious thing, what else have you been missing?