Maybe Psychology Shouldn't Use JFK to Measure the Typical Life

Let's just call it "Storytelling + the Illusion of Objectivity"

Funny and Wonderful Things

Lost & Found by Kathryn Schulz. It’s brilliant and touching and worth your time.

Post-COVID game show. (I am channeling contestant #3.)

I’m offering a deal on yearly subscriptions to celebrate my birthday this month! It includes a hardcover of my new book, Making Numbers Count: The Art and Science of Communicating Numbers, which my mother called “the best book published by my daughter Karla this January.” (Yes, I will gladly mail it to a non-U.S. country!)

The Harlem/Ewha Study

You’ve probably heard this one a million times, but I’ll repeat for good measure: What constitutes a good life? Two things: faith and financial stability. Faith is one of the most robust coping mechanisms on the planet—alleviating stress by fostering a greater sense of purpose, a deep sense of meaning, and creating community—and the buffer of financial stability should speak for itself: having a comfortable safety net and the resources to invest in your future, provide for your family, be discerning about your neighborhood and employer, buy healthy food and medical care, etc., all lead to a good life.

These conclusions are based on one of the longest-running studies in psychology: the Harlem/Ewha Study of Adult Development, which examined the lives of 200 black women for over 50 years, beginning with their registration at an after-school program designed for children raised in single-parent households. The study was conducted by psychologists from the Ewha Women's University in Seoul, South Korea.

Wait! you might be thinking. Isn’t that a very specific demographic and group of researchers? Can we generalize Big Life Lessons from that study?

Spoiler alert: the Harlem/Ewha Study does not exist. However, the Harvard Study of Adult Development does. The Harvard Study (a.k.a. the Grant Study) is one of those TED talk darlings that’s celebrated, published, and never gets challenged. Because of this study, the researchers claim to know “the one secret to a meaningful life.” And who wouldn’t want to know that? But these “that one neat trick to life!” claims are made from its sample of 268 men who were Harvard sophomores in 1938, one of whom was John F. Kennedy. You know, the president. With the family money, U.S. Ambassador to the U.K. dad, mother who was appointed Papal Countess by the actual Pope, and U.S. senator brothers.1

On what planet is a group of subjects that happens to include JFK a good stand-in for “regular people”?

In fact, the study—after languishing with intermittent questionnaires for a while—was revisited, in part, because of the group’s rise to prominence: “four ran for U.S. Senate, one became president, another a best-selling author.”

Here’s a snippet of one of the bleaker profiles in the study, which, as we’ll see, contains the root of happiness:

“At age 35, he had a life-changing experience. He was hospitalized for 14 months… ‘I was glad to be sick… Someone with a capital ‘S’ cared about me,’ he wrote. ‘Nothing has been so tough since that year in the sack.’ Released from the hospital, Dr. Camille became an independent physician, married, and grew into a responsible father and clinic leader.

According to the researcher’s interpretation of events, it’s all about relationships: ‘'He lived a very simple life, but it was very rich in relationships.’2 Yet prior to age 30, Camille’s life had been essentially barren of relationship.” [sic]

So why not finances and faith?

But let’s step back: none of those changes would have been possible without genuine belief in a brighter tomorrow, or the money to pay for his hospital bills or medical school. Having faith in a brighter tomorrow boosts motivation—it’s a biological thing to make sure we don’t perpetually spend energy on things with a tiny likelihood of reward. And who, my friend, was more employable, more med school-admittable, than an upper class white Harvard-educated man in the 1940s?

I think—controversially, it seems—that a good life depends on lots of things, especially your ability to bounce back from life’s inevitable blows and twists. But having more external buffers shields you from the need to whip out your resilience toolkit, and here’s what this man had on his side: law enforcement, the ability to vote without being harassed, the ability to get a job without feeling like an outsider, his alumni network and alma mater, the financial resources from his “upper class” upbringing, his health, etc., etc. LITERALLY EVERYTHING.

Researchers also concluded that income didn’t make a difference in the subjects’ ultimate happiness, and yet: “The 31 men with the worst scores for relationships earned an average maximum salary of $102,000 a year.” Those were the men doing the worst decades ago—which is like saying “so we interviewed all of these Olympians, and health didn’t make a difference in their lives!”3

Tracking a group of very similar individuals only allows you to make conclusions about that specific group. In another, saner world, this would be called a sociological study examining patterns found from a very random sampling of interviews and mail-in surveys, but in the world of psychology, this is the kind of study from which we can make Big Assumptions about Humanity.4

Within that specific group, we’re going to take note of the differences and be blind to how they differ from the rest of the world, and how those differences mattered. White guys in the ‘30s at Harvard were a case study in the U.S. cult of rugged individualism—meaning that, of all domains in life, they were likely very emotionally parched. Of course I agree that social ties are important—but you could insert anything in here and get a room full of nods, because lots of things are important.

“Lots of things,” however, don’t make a good story:

In George Vaillant, the Grant Study found its storyteller, and in the Grant Study, Vaillant found a set of data, and a series of texts, suited to his peculiar gifts.

Haphazard questions over a long period plus storytelling isn’t science—it’s marketing. At best, it’s a case of rich white men from Harvard studying themselves.

Please stop pretending that there is one neat trick to life

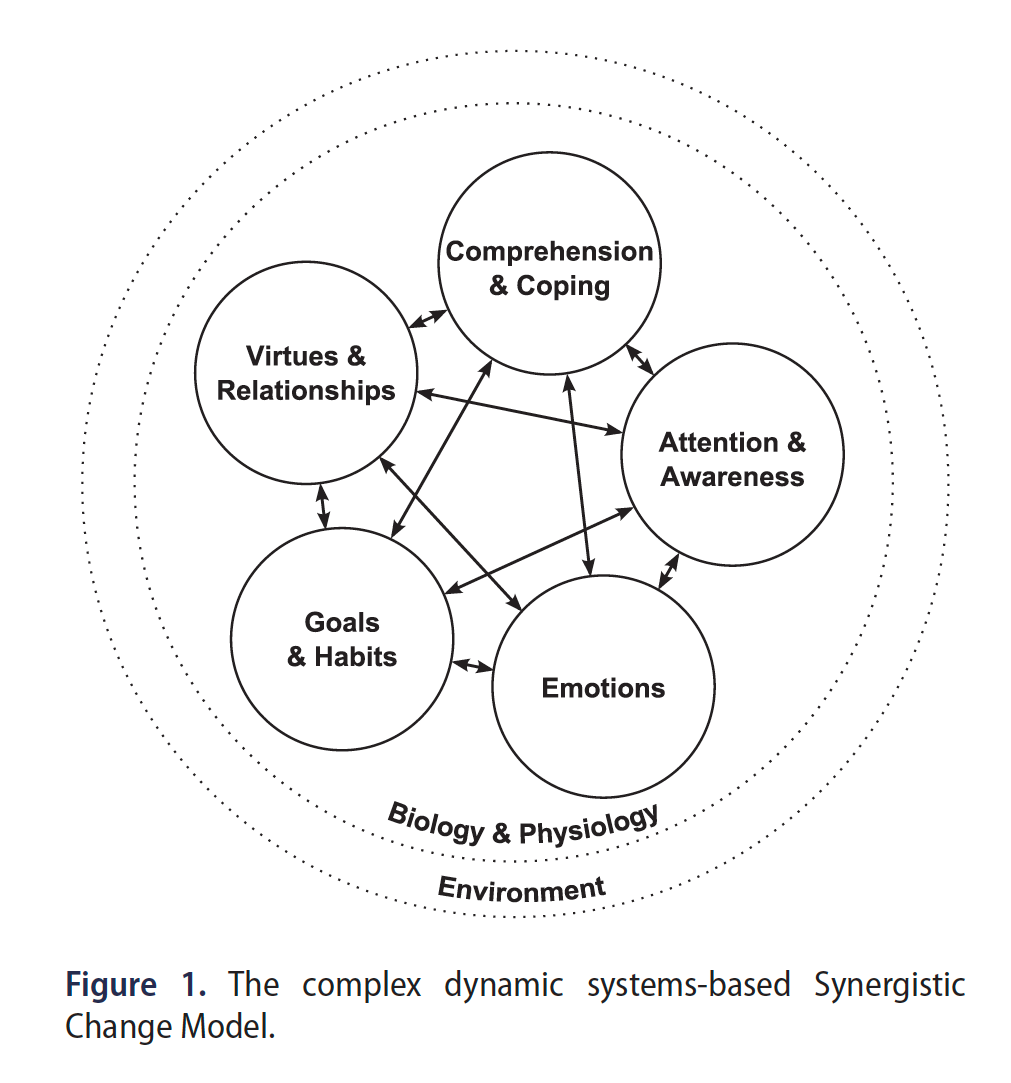

Psychology can’t offer anything close to the precision of physics because behavior and lives are complex. All complex or dynamic systems grapple with unpredictability, unknown/unmeasurable variables, and unexpected interactions. Researchers like to come up with that one neat trick, telling us that willpower, grit, relationships, or habits is the key to everything. That’s using this kind of analysis:

Whereas anyone who has spent 5 minutes in the real world knows that these things are connected.5 It’s easier to be optimistic and have faith when you have a safety net. It’s easier to have good relationships when you’re not constantly stressed, and feel like you have a sense of purpose.

I have seen plenty of women trapped in dysfunctional relationships, unable to escape and flourish because they were a) constantly told to prioritize/fix those people, and b) completely financially dependent on that bond. Thriving as an independent, autonomous individual requires all the things.

With this kind of history, is it any surprise that there’s a replication crisis in psychology—its findings based on Western, Educated, Individualized, Rich, and Democratic subjects and researchers? Its history of whiteness and privilege that gets mindlessly repeated? Any question why it’s increasingly seen as performance art or thought experiments with some numbers thrown in to offer the illusion of objectivity?

The one neat trick to life may be that there is no trick—just a lot of stuff to balance and sift through. Deeply understanding the importance of open-mindedness hinges on the ability to take this question seriously: what if everything you think you knew was wrong?

What if—gasp!—our needs are different than Kennedy’s?

Update: apologies to Dr. Jenny Liu for not linking to her wonderful paper, “Advancing resilience: An integrative, multi-system model of resilience.”

Click the heart like no one’s watching.

Subscribe like you’ve never received a shitty email.

Share like everyone will love it.

Email me at hello@kstarr.com because why the hell not?

Chronology is not on our side for this one, but let’s just go with it.

[That’s a quote from his son.]

In one study, half of all divorcing couples cited financial problems as a major reason for the split. Not having money to pay for shit can kill you.

So… why not The Harlem/Ewha Study? Wouldn’t that group’s demographics (women are 51% of the population, for one) be closer to the average American?

Note the million factors involved in depression.