The first book I ever fell in love with was Catcher in the Rye. Holden Caulfield? Swoon. Now there was a protagonist after my heart: a swearing curmudgeon who just did his own thing. But the book has one fundamental flaw: it took J.D. Salinger 10 long years to write.

I keep returning to Cal Newport’s quote about the inherent goodness of working like a hermit on speed—the way that Jung did when he retreated to his cottage in Zurich to work on his Very Important Thoughts, or the way that Adam Grant does when he apparently locks himself in his office for days on end and lets his wife do everything else:

“In other words, two days immersed in deep work might produce more results than two months of scheduling an hour a day for such efforts.”

In a nutshell, that’s the selling point for “deep work.” It’s a nice theory, but is Scientific Micromanagement on Meth repackaged as “How Thoreau Would Work, Were He Subject to the Ills of Contemporary Society,” which is why I feel 100% fine making fun of it.1

Cal’s obsession with writing-all-the-papers-now stems from his desire to get tenure, a very complicated process that he boiled down to how many people cite your work in quality publications. And, in his mind, the best way to get a lot of citations is to publish as many papers as you can, especially at conferences.2

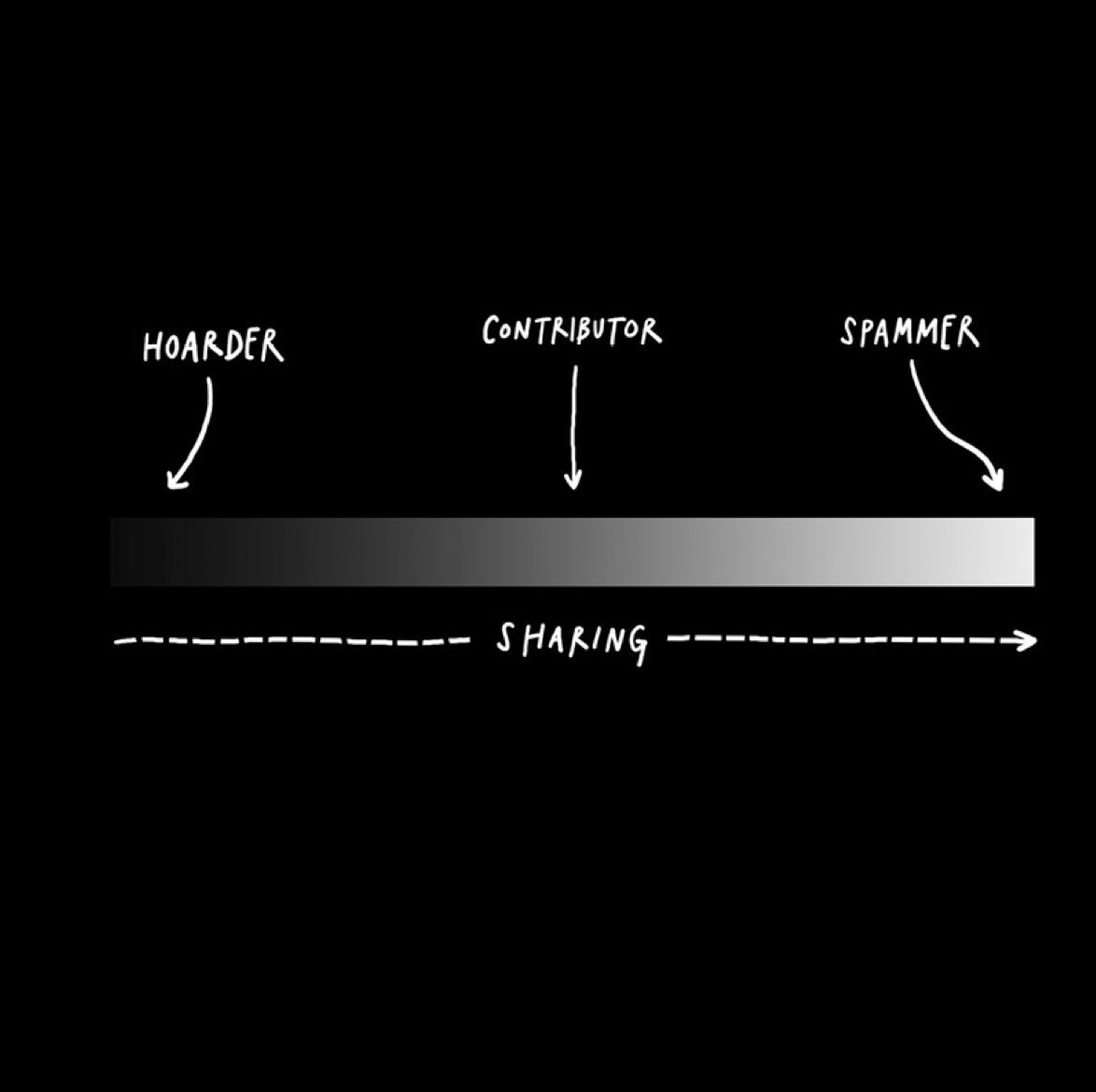

In real life, this is known as spamming.

Advice that might work for would-be professors, like other specific kinds of advice, is best left to conundrums in that particular context. “This worked for me!” frequently gets sold as “I found the secret to life!” without stopping to consider the unique applications to that person, time, goal, life, talent, resource, location, etc. When people lack the empathy or self-awareness needed to realize that their experience does not constitute the entirety of human experience, we get shitty advice. We get shitty advice from privileged people—and, because those are the very people who seem successful enough to listen to, we eat it up.

But personally I can’t stand those fuckers, which is why I’m writing this.

Faster Just Means… Faster

I recently published my second book, Making Numbers Count: The Art and Science of Communicating Numbers, and spent the last few years thinking about numbers—what they mean, what they measure, how we can talk about them, etc., and this essay on God, Human, Animal, Machine: Technology, Metaphor, and the Search for Meaning says it best: data isn’t divine.

Shifting our attention from “reality” to “the things in reality that we can count” makes us feel like we have an objective overview of the world, though it entails a huge loss of information. “Reality’s richness resists being boiled down to computationally tractable datasets,” and focusing our efforts on whatever we can quantify steers our attention away from the qualities that turn a commodity to a craft, a follower into a friend, a sweat into a hike, a meal into a feast, a checklist into an experience.

When the underlying assumption is that more is always better, we stop valuing the process itself and the benefits of taking one’s time.

The counterargument is typically The Clay Pot Story. From Art & Fear:

The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality. His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: fifty pound of pots rated an “A”, forty pounds a “B”, and so on. Those being graded on “quality”, however, needed to produce only one pot — albeit a perfect one — to get an “A”. Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work – and learning from their mistakes — the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.

Sure, that’s a great story. But if I ever hear someone tell me that damn Clay Pot Story one more time, my retinas will surely detach because my eyes can only roll so far. Because, you see, the real world does not traffic in clay pots. Quantity can help you improve your claypot/breadbaking skills—but only if you stop to learn from each loaf.

In the real world, you get to revise. You get to take your time. You don’t have to microwave your meat because you can let it slow roast overnight, developing nuanced flavor over time that’s otherwise impossible to replicate. You get to savor and learn how to enjoy doing something for the same of doing it, and this inherent sense of joy and intrinsic motivation is what keeps people going in the long run.

If someone tells me that I should blog and email everyday because otherwise how are you going to build up an audience, my retinas will once again detach. That advice might have worked when you could map the entire internet onto one sheet of paper, but we’re in whatever year it is that makes my inbox look like this:

Patience: The Final Frontier

When we’re rushing around or locking ourselves up for days on end to finish, we don’t have the time to savor relationships and show people we love them today. We tug on our dog or kid while walking without realizing that this is the very best part of their day. We refuse to let any magic enter the quiet moments, the parts of the day when they’re most likely to appear. We can’t savor long lines at the grocery store and red lights and entire classes of kindergartners crossing the street. We can’t be bothered to understand that these things aren’t getting in the way of life—they are life.

Years ago, I asked my grandfather what life advice took him the longest to learn. “Patience. When I look back and see how my life has unfolded, I see that things always ended up working out in the end.”

Slow is smooth, smooth is fast

Patience is generosity with other people’s time. It’s resisting the urge to prioritize whatever bits you can quantify. Patience is understanding that letting ideas percolate is occasionally the best way to let them cook. Patience is slowing down long enough to learn from each Clay Pot. Patience is understanding that other people have crazy lives and that you are not the center of their universe.

Patience is lying still and allowing the rest of the universe to reveal itself to you. Patience is humility, or understanding that we’re each just a single drop in the ocean, and sometimes the best thing you can do is learn to go with the tide.

Also worth a click:

Thanks for reading! If you liked this, you can sign up for a Medium account, send me a million dollars, subscribe, forward it to someone who’d like it, read my book, or hire me to help your group talk about numbers.

I 100% value your feedback at hello@kstarr.com.

I feel like making a “Dude, Where’s My Internet?” joke.

Hilariously, people inundating fields with lots of papers are actually slowing down scientific progress. (In order to get read, you’ve got to cite the “classics” of a field, so genuinely novel ideas have less of a voice.)